Indentured Students is a blog whose only aim is to inform , educate and empower college students burdened by the 21st century form of indenture, student loans. This is a space for you to exchange ideas and information about the huge size of this problem and how best to handle it.

Sunday, November 11, 2012

Various Repayment Options

Default is a rare case for Pace graduates. Over the past 3 years only 4.8% of those that had initiated payment have defaulted i.e. stopped payment within 270 days of their first repayment.That might not sound high statistically but it does represent 117 students whose financial life has been dealt a serious blow that will be very difficult to overcome.

I know that no one defaults unless they are at a dead end and they have no other choice. If that is the case then one must accept the consequences and adjust as best as possible to the tough conditions. But this is rarely the case. Many of those that default are not aware of the variety of options available to them.The students themselves are to blame for not being totally informed but the blame is also to be shared by the lending institutions that fail to keep the borrowers abreast of all the new developments as well as the educational institutions themselves who have also failed to keep their former students up to date.

The following example might help shed light on why is it that I feel strongly that no student should ever default: Let us assume that Jane is single, owes #50,000 in Federal Student Loans, has an AGI of $30,000 and that the loans carry a 6.8%. Let us also assume that Jane received her first loan after Sept30, 2007 and that she also received a loan after Sept. 30 2011.

What are some of her repayment option?

A Standard Repayment plans: $575.40 / month for 120 payments

347.04 / month for 300 payments

B IBR (Income Based Repayment) $166.00 / month for 300 payments

C Pay-As-You-Earn $110.00/ month capped at 10% of Income and forgivness of

the balance after 300 payments.

There are a few other options but as the above example illustrates very clearly it is very difficult to justify default given all these repayment options.

Saturday, November 3, 2012

Default rates: National vs Pace University

That there is a student loan problem is not debatable. The overall sum of Student Loans is increasing at an unsustainable rate while the ability of borrowers to service this debt is becoming more difficult every day. The most common yardstick to measure the above is called CDR, Cohort Default Rate, which is a measure of the proportion of Federal Student borrowers who default on their obligations within a specific time after the repayment process begins. The 2 year CDR used to be the most common standard until the passage of the High Education Opportunity Act of 2008 which recommended the adoption of a 3 year CDR as a better measure of the default problem.

Default is defined to be a time period of 9 months of nonpayments. The most recent data shows that the problem of default is becoming more acute. The two year CDR has registered an increase to 9.1 % while the three year CDR has risen nationally to13.4%. It must be noted that almost half of the defaults; 47%; are recorded against for -profit-colleges whose total student enrollment accounts only to 13% of the national student body. The record of the not-for-profit institutions ; such as Pace University; is much better. As a group the not-for-profit have 15% of the students and account for 13% of the defaults

The record for Pace students is one of the best in the nation. The last three 2 year CDR for Pace students shows a CDR of 3.4% for those students who started repayments in 2010. That unfortunately is slightly higher than the 2 year CDR for those who started their repayment in 2009 and who had a default rate of only 2.4%.

A high CDR reflects bad on the institution as well. The availability of funds for its students will be affected negatively. The rationale being that the institution is not exercising enough caution in its admission policies and is allowing its students to carry loan levels that are beyond their capabilities.

Pace University students have an enviable 3 year CDR of only 4.8%. Yet even that low level represents 117 students out of 2399 who have defaulted within 270 days of when they started repayment. The consequences for the student can be rather severe and so must be avoided at all costs , whenever possible. A default will create a bad credit report for life, it could trigger garnished wages and might even affect Income Tax refunds and Social Security benefits.

What is sad about the above situation in which these 117 students find themselves is the possibility that they have not been properly informed of all the options available to them.It is very high likely that each of these students is eligible for the Income Based Repayment program, IBR, which has been available since 2009. Under IBR, loan repayments are caped at a manageble proportion of income and the balance is forgiven after 25 years of payment. If only one of the 117 Pace students who is in default was not properly informed of his/her options then that is a travesty.

Wednesday, October 24, 2012

From The Lions Mouth

Debt Déjà Vu For Students

Financial institutions expect borrowers to hold up their end of the bargain when it comes to mortgages and student loans. Shouldn't we expect the same of them?

Before this year's mortgage settlement between regulators and large banks, there were reports of mismanagement by mortgage servicers caused great harm. Improper foreclosures reportedly wreaked havoc on families - including members of the military, hundreds of whom faced illegal foreclosures, many while they were deployed.

Student borrowers whose cases are mishandled can also suffer significant damage. A young borrower facing default and the resulting scar on her credit record could find her dreams further out of reach. Many distressed borrowers worry that they will never be able to buy a home or save enough to start a family. Some have a hard time getting work because prospective employers check their credit.

Last week, I presented a report to Congress on shoddy loan servicing practices that may not be limited to the mortgage market. Student borrowers have reported servicing detours and dead ends that bear an uncanny resemblance to the problems homeowners have faced. And as with the mortgage market, there are reports that military families also got the runaround.

The parallels run deep. As in the mortgage market, student borrowers report that some lenders engaged in aggressive marketing and risky underwriting. Now many borrowers have finished school and find that they can't pay the bills.

Based on the complaints of borrowers, it appears that many servicers depend on being able to extract loan repayment quickly and cheaply, which works when everyone can pay. Although even struggling borrowers tend to look for ways to meet their obligations, too many feel trapped by terms and conditions that servicers won't change.

In tough times, consumers need clarity, not confusion. While loan servicers can't just let borrowers off the hook, they should be able to help them understand their options. But too many borrowers say they can't get consistent answers to simple questions. Instead, they find themselves ping-ponged around departments and talking to multiple people to no avail.

Like mortgages, many student loans were packaged, sliced, and diced into securities. Sometimes consumers are the collateral damage when transfers among servicers don't go smoothly. While consumers can't avoid paying up by claiming they lost paperwork, it seems some servicers are using that excuse to justify poor service.

So why can't the market solve this? When consumers get bad service at, say, a restaurant, they don't go back. But if loan servicing is bad, consumers have to grin and bear it. They rarely get a say on whether a lender outsources its servicing, and servicers are more accountable to lenders. With few viable options for refinancing, ordinary market forces don't apply.

Last year, total outstanding student debt crossed the $1 trillion mark, with private loans comprising $150 billion of that. With more than 850,000 private student loans in default and even more in delinquency, there is a lot of work to be done to make sure these borrowers aren't sentenced to a lifetime of permanent financial distress.

Our student debt problem didn't start overnight, and it won't disappear quickly, either. But the U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has recommended reforms to assure that past risky practices aren't repeated in the next generation.

While parents might be struggling with mortgages, let's not forget the others caught up in the crisis. They're entering the labor market more burdened than any generation before. That burden shouldn't be compounded by a system that shortchanges them on basic customer service, like making sure payments are processed and records aren't lost. We must keep an eye on the student-loan market to prevent lasting harm to a generation of borrowers and to the economy.

Rohit Chopra is the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau's student loan ombudsman.

Tuesday, October 23, 2012

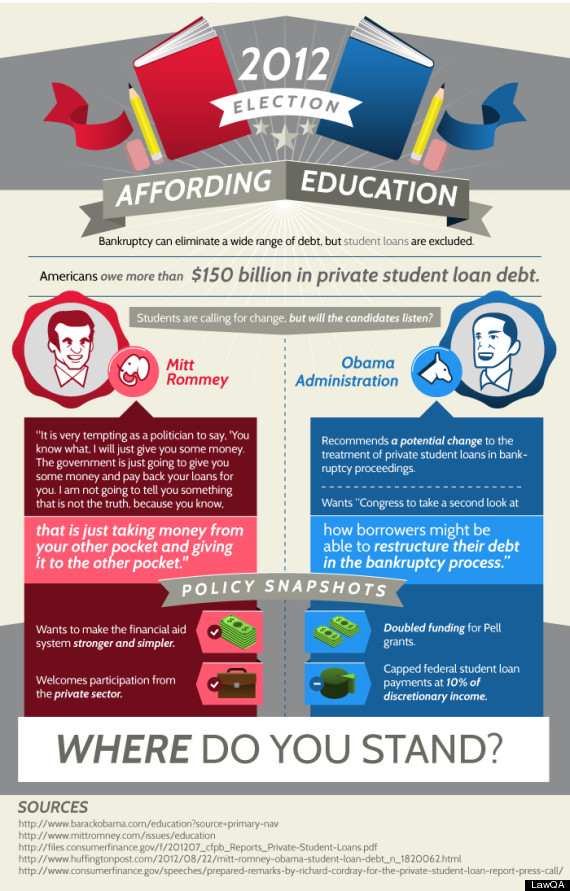

Obama vs Romney

The presidential elections is less than two weeks away. The voters are told , every presidential cycle, that the difference between the candidates has never been this great and that this election is the most important that we have seen in a long time. Well what did you expect them to say? The two parties are essentially copies of each other and it makes no difference who is elected!!! :-)

Ralph Nader never tired of telling us that the two political parties are a duopoly i.e. a market controlled by two firms/organizations. Obviously many think that the Nader analysis is faulty and that we do have a fairly competitive electoral system that presents us with a real choice.

Whether you believe in the Nader hypothesis or its opposite is not important for this post. If you are a student who is carrying the financial burden created by a Student Loan then each of the two major parties has a rather different plan to deal with the over $1 Trillion student debt problem.

I do not intend to do your thinking for you. You look at the major items that each of the two candidates supports and decide which of the two plans suits you and the country best. Do not forget to vote.

Click on graphic to enlarge

Wednesday, October 17, 2012

Student Loan Servicing Complaints Rise

Here we go again. I sure hope that we prove Winston Churchill wrong this time by learning from history because if we do not then the potential outcome could be disasterous to all of us, maybe the repercussions could even go global. What is at stake is nothing short of the economic viability of the US economy and whether it could be dragged into another recession although it has not fully recovered yet from the close call of the previous one.

Tuesday, October 9, 2012

IRS Must Get Its Pound Of Flesh

Many students accumulate student debt loans that cannot possibly paid back from their regular monthly wages. This is a serious problem since, as we have stated many times previously, these debts cannot be written off through bankruptcy. So what is the solution, if any?

Their are a number of government options that limit the portion of income to be paid in debt service for these loans in addition to the fact that some public service would entitle the provider to a student loan write off after a certain period of service. The best alternative is contained in HR 7140 which has not become law yet. It is my sincere belief that every student must contact his/her representative in congress and lend support for this great bill. It will make student loan write offs easier especially after public service.

We have dealt with all the above previously so why the repetition? The only aim of this post is to stress that as good as write off are at times they are much less than they appear to be. This post is not going to deal with the specifics since each loan and each program is subject to slightly different provisions. Our aim however is to remind the student loan borrower that in many cases the IRS will treat a write-off as income. Yes, you heard it right. It might take you ten years to qualify to say a $40,000 right off but the IRS will consider that as income and will increase your taxes for that year accordingly. It is true, at least in this case, that no one can avoid death and taxes., especially those who carry student loans.

Monday, October 8, 2012

Indentured Servitude

The following long article appeared on the AAUP web site. It is very relevant and informative.

Discussion of academic freedom usually focuses on faculty, and it usually refers to speech. That is the gist of the 1915 General Report of the Committee on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure, appearing in the inaugural AAUP Bulletin as a kind of mission statement. The report invokes the ideals of the German tradition, “Lehrfreiheit and Lernfreiheit,” or freedom of teachers and freedom of students, in the first sentence, but the remainder of the document talks about the freedom of professors. That is because its authors were responding to their particular situation, notably the firing of Professor Edward A. Ross from Stanford University for his statements about railroad monopolies, as well as to the position of US college students, who were not subject to state control as they were in the German system. Given the conditions of the American system of higher education— decentralized and meeting diverse needs, with liberal admissions requirements and relatively low tuition, and subject to ordinary speech protections—it was assumed that students had a good deal of freedom.

That assumption has persisted through most of the century, as higher education has opened to an expanding body of students. However, over the past thirty years, students’ freedom has been progressively curtailed—not in their immediate rights to speech but in their material circumstances. Now, two-thirds of American college students graduate with substantial debt, averaging nearly $30,000 (if one includes charge cards) in 2008 and rising, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics and other sources.

In my view, the growth in debt has ushered in a system of bondage similar in practical terms, as well as in principle, to indentured servitude. The analogy to indenture might seem exaggerated but actually has a great deal of resonance. Student debt binds individuals for a significant part of their future work lives. It encumbers job and life choices, and it permeates everyday experience with concern over the monthly chit. It also takes a page from indenture in the extensive brokerage system it has bred, from which more than four thousand banks take profit (even when the loans originate with the federal government, they are still serviced by banks, and banks service an escalating number of private loans). At its core, student debt is a labor issue, just as colonial indenture was, subsisting off the desire of those less privileged to gain better opportunities in exchange for their future labor. One of the goals of the planners of the US university system after World War II was to displace what they saw as an aristocracy; instead, they promoted equal opportunity in order to build America through its best talent. The new tide of student debt reinforces rather than dissolves the discriminations of class. Finally, it violates the spirit of American freedom in leading those less wealthy to bind their futures.

Here are some ways that college student loan debt revives indentured servitude.

Prevalence. Contrary to the usual image of freedom-seeking Puritans in New England, between one-half and two-thirds of all white immigrants to the British colonies arrived under indenture, according to the economic historian David W. Galenson, totaling 300,000 to 400,000 people. Similarly, college student loan debt is now a prevalent mode of financing higher education, resorted to by two-thirds of students who attend. If upwards of 70 percent of Americans attend college at some point, it thus shackles not an unfortunate few but half the rising population.

Amounts. Indenture was a common practice in seventeenth-century England, but its terms were relatively short, typically a year, and closely regulated by law. The innovation of the Virginia Company, to garner cheap labor in the colonies, extended the practice of indenture to America, but at a much higher obligation of four to seven years, because of the added cost of passage and boarding immigrants, and also the added cost of the brokerage system that arose around it.

Student debt has similarly morphed from relatively small amounts to sizeable ones. The average federal loan debt of a graduating senior in 2008 was $24,000. That was a marked rise from ten years before, but even more tellingly, it was an astronomical rise from twenty-five years ago, when average federal loan debt was less than $2,000. Also consider that many people have significantly more than the average debt—25 percent of federal borrowers had more than $30,000 in student loans, and 14 percent owed more than $40,000 in 2008. Added to federal loans are charge cards, which averaged $4,100 for graduating seniors in 2008, and private loans, which by 2008 were taken by 14 percent of students (up from 1 percent in 1996) and totaled $17.1 billion, a disturbingly large amount in addition to the $68.6 billion for federal loans. Finally, for more than 60 percent of those continuing their education, graduate student debt more than doubled in the past decade, to a 2008 median of about $25,000 for master’s degrees, $52,000 for doctorates, and $80,000 for professional degrees. That is on top of undergraduate debt.

Length of term. Student debt is a long-term commitment— standard Stafford Loans amortize over fifteen years. With consolidation or refinancing, the term frequently extends to thirty years—in other words, for many returning students or graduate students, until retirement age. It is not a brief, transitory bond, say, of a year for those indentured in England, or of 1980s student debtors, who might have owed $2,000.

Transport to work. Student indebtedness is premised on the idea of transport to a job—now the figurative transport over the seas of higher education to attain the shores of credentials deemed necessary for a middle-class job. The cost of transport is borne by the laborer, so, in effect, an individual has to pay for the opportunity to work. If you add the daunting number of hours that students work, one twist of the current system is that servitude begins on ship. Undergraduates at state universities work more than twenty hours a week, according to Marc Bousquet’s work. Tom Mortenson, an education policy analyst, provides a telling comparison of hours a week required at minimum wage to pay tuition, which have grown roughly from twenty hours a week before 1980 to more than fifty hours a week now at public universities and colleges, and from about forty hours to a stunning 130 at private institutions.

Personal contracts. “Indenture” designates a practice of making contracts before signatures were common (they were torn, the tear analogous to the unique shape of a person’s bite, and each party held half, so they could be verified by their match); student debt reinstitutes a system of contracts that bind a rising majority of Americans. Like indenture, the debt is secured not by property, as most loans such as those for cars or houses are, but by the person. Student loan debt “financializes” the person, in the phrase of social critic Randy Martin, who diagnoses this strategy as a central one of contemporary venture capital, displacing risk to individuals rather than employers or society. It was also a strategy of colonial indenture.

Limited recourse. Contracts for federal student loans stipulate severe penalties and are virtually unbreakable, forgiven not in bankruptcy but only in death, and they are enforced by severe measures, such as garnishing wages and other legal sanctions, with little recourse. In England, indenture was regulated by law and servants had recourse in court, but one of the pernicious aspects of colonial indenture was that there was little recourse in the new colonies. Alan Collinge, founder of the grassroots organization Student Loan Justice and author of The Student Loan Scam, has proposed that student debt be forgiven in bankruptcy as any other personal loan would be.

Class. Student debt primarily bears on those with less family wealth, just as indenture drew on the less-privileged classes. That this would be a practice in early modern Britain, before modern democracy, is not entirely surprising; it is more disturbing in the United States, where we eschew the determining force of class. The one-third of students without student debt face much different futures, and are far more likely to pursue graduate and professional degrees (for example, three-quarters of those receiving doctorates in 2004 had no undergraduate debt, and, according to a 2002 Nellie Mae survey, 40 percent of those not pursuing graduate school attributed their choice to debt).

Youth. Student debt applies primarily to younger people, as indenture did. One of the more troubling aspects of student debt is that it is not an isolated hurdle but often the first step down a slope of debt and difficulty, as Tamara Draut, vice president of policy and programs at Demos, shows in Strapped: Why America’s 20- and 30-Somethings Can’t Get Ahead. Added to that burden are shrinking job prospects and historically higher housing payments. The American dream, and specifically the post–World War II dream of equal opportunity opened by higher education, has been curtailed for many of the rising generation.

Brokers. Colonial indenture prompted a system in which merchants or brokers in England’s ports signed prospective workers, then sold the contracts to shippers or colonial landowners, who in turn could resell the contracts. Student debt similarly has fueled an extensive financial services system. The lender pays the fare to the college, and thereafter the contracts are circulated among Sallie Mae, Nellie Mae, and others. Sallie Mae was created as a federal nonprofit corporation, but it became an entirely private (and highly profitable) corporation in 2004.

State policy. The British Crown gave authority to the Virginia Company; the US federal government authorizes current lending enterprises and, even more lucratively for banks, underwrites their risk in guaranteeing the loans (the Virginia Company received no such largesse and went bankrupt). Since the 1990s, federal aid has funneled more to student loans than any other form of aid. Loans might be helpful, but they are a rather ambivalent form of “aid.”

These points show the troubling overlap of indentured servitude and student indebtedness. While indenture was more direct and severe, akin to placing someone in stocks, it was the product of a rigidly classed, semifeudal world that predated modern democracies. Student debt is more flexible, varied in application, and amorphous in effects—a product of the postmodern world—but it revives the spirit of indenture in promulgating class privilege and class subservience. What is most troubling is that it represents a shift in basic political principle. It turns away from the democratic impetus of modern American society, which promoted equality through higher education, especially after World War II. The 1947 Report of the President’s Commission on Education, which ushered in the vast expansion of our colleges and universities, emphasized that “free and universal access to education must be a major goal in American education.” Otherwise, the commission warned, “if the ladder of educational opportunity rises high at the doors of some youth and scarcely rises at the doors of others, while at the same time formal education is made a prerequisite to occupational and social advance, then education may become the means, not of eliminating race and class distinctions, but of deepening them.”

The commission’s goal was not only to promote equality but also to strengthen the United States—and, by all accounts, American society prospered. Current student debt, encumbering so many of the rising generation, has built a roadblock to the American ideal, squanders the resource of those impeded from pursuing degrees who otherwise would make excellent doctors or professors or engineers, and creates a culture of debt and constraint.

The arguments for the rightness of student loan debt are similar to the arguments for the benefits of indenture. One holds that it is a question of supply and demand—many people want higher education, thus driving up the price. This view doesn’t hold water because the demand for higher education in the years following World War II through the 1970s was proportionately the highest of any time, as student enrollments doubled and tripled, but the supply was cheap and largely state funded. Then, higher education was much more substantially funded through public sources, both state and federal; now the expense has been privatized, transferred to students and their families.

University of Chicago economist David Galenson argues in his work on colonial servitude that “long terms did not imply exploitation” because those terms were only fitting for the high cost of transport; because more productive servants, or those placed in undesirable areas, could lessen their terms; and because some servants went on to prosper. He does not mention the high rate of death, the many cases of abuse, the draconian extension of contracts by unethical planters, or simply what term would be an appropriate maximum for any person in a free society to be bound, even if he or she agreed to the contract. Galenson also ignores the underlying political questions: Is it appropriate that people, especially those entering the adult world, might take on such a longterm constraint? Can people make a rational choice for a term they might not realistically imagine? Even if one doesn’t question the principle of indenture, what is an appropriate cap for its amounts and term? One of the more haunting findings of the 2002 Nellie Mae survey was that 54 percent said that they would have borrowed less if they had to do it again, up from 31 percent ten years before, which is still substantial (and, one can extrapolate, increased from 1980). The percentage of borrowers making this informed judgment will surely climb as debt continues to rise.

Some economists justify college student loan debt in terms similar to Galenson’s. One prominent argument holds that because college graduates have averaged roughly $1 million more in salary over the course of their careers than those with less education, it is rational and right that they accumulate substantial debt to start their careers. However, while many graduates make statistically high salaries, the experiences of those who have taken on debt vary a great deal: some accrue debt but don’t graduate; some graduate but, with degrees in the humanities or education, for example, are unlikely to make a high salary; more and more students are having difficulty finding a high-paying job; and the amount that people who have a college degree make over a lifetime has been declining. A degree is no longer the guaranteed ticket to wealth that it once was. An economic balance sheet also ignores the fundamental question of the ethics of requiring debt of those who desire higher education, as well as the fairness of its distribution to those often younger and less privileged.

Over the past few years, there has been more attention to the problem of student loan debt, but most of the solutions, such as Income-Based Repayment, or IBR, are stopgaps that don’t impinge on the basic terms of the system. The system needs wholesale change.

College student loan debt perverts the aims of higher education, whether those aims are to grant freedom of intellectual exploration, to cultivate merit and thereby mitigate the inequitable effects of class, or, in the most utilitarian scheme, to provide students with a head start into the adult work world. In practice, debt shackles students with long-term loan payments, constraining their freedom of choice of jobs and career. It also constrains their everyday lives after graduating, as they bear the weight of the monthly tab that stays with them long after their college days. The AAUP should consider student debt a major threat to academic freedom and make the abolition of student debt one of its major policy platforms.

A Note on Sources

The major source of data on student debt is the Digest of Education Statistics for postsecondary education published by the National Center for Education Statistics of the US Department of Education. The center conducts the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study every four years; the most recent data are from 2007–08. The Project on Student Debt publishes useful reports digesting and processing information related to key aspects of student debt. The loan industry also collects a good deal of information—for example, Sallie Mae’s How Undergraduates Use Credit Cards (2009)—about the contiguous issue of charge-card debt.

Jeffrey J. Williams writes on contemporary fiction, modern criticism and theory, and the university. He is a coeditor of the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism and was editor of the minnesota review from 1992 to 2010. He is professor of English and of literary and cultural studies at Carnegie Mellon University. His e-mail address is jwill@andrew.cmu.edu.

Academic Freedom and Indentured Students

Escalating student debt is a kind of bondage.

By Jeffrey J. Williams

Discussion of academic freedom usually focuses on faculty, and it usually refers to speech. That is the gist of the 1915 General Report of the Committee on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure, appearing in the inaugural AAUP Bulletin as a kind of mission statement. The report invokes the ideals of the German tradition, “Lehrfreiheit and Lernfreiheit,” or freedom of teachers and freedom of students, in the first sentence, but the remainder of the document talks about the freedom of professors. That is because its authors were responding to their particular situation, notably the firing of Professor Edward A. Ross from Stanford University for his statements about railroad monopolies, as well as to the position of US college students, who were not subject to state control as they were in the German system. Given the conditions of the American system of higher education— decentralized and meeting diverse needs, with liberal admissions requirements and relatively low tuition, and subject to ordinary speech protections—it was assumed that students had a good deal of freedom.

That assumption has persisted through most of the century, as higher education has opened to an expanding body of students. However, over the past thirty years, students’ freedom has been progressively curtailed—not in their immediate rights to speech but in their material circumstances. Now, two-thirds of American college students graduate with substantial debt, averaging nearly $30,000 (if one includes charge cards) in 2008 and rising, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics and other sources.

In my view, the growth in debt has ushered in a system of bondage similar in practical terms, as well as in principle, to indentured servitude. The analogy to indenture might seem exaggerated but actually has a great deal of resonance. Student debt binds individuals for a significant part of their future work lives. It encumbers job and life choices, and it permeates everyday experience with concern over the monthly chit. It also takes a page from indenture in the extensive brokerage system it has bred, from which more than four thousand banks take profit (even when the loans originate with the federal government, they are still serviced by banks, and banks service an escalating number of private loans). At its core, student debt is a labor issue, just as colonial indenture was, subsisting off the desire of those less privileged to gain better opportunities in exchange for their future labor. One of the goals of the planners of the US university system after World War II was to displace what they saw as an aristocracy; instead, they promoted equal opportunity in order to build America through its best talent. The new tide of student debt reinforces rather than dissolves the discriminations of class. Finally, it violates the spirit of American freedom in leading those less wealthy to bind their futures.

Here are some ways that college student loan debt revives indentured servitude.

Prevalence. Contrary to the usual image of freedom-seeking Puritans in New England, between one-half and two-thirds of all white immigrants to the British colonies arrived under indenture, according to the economic historian David W. Galenson, totaling 300,000 to 400,000 people. Similarly, college student loan debt is now a prevalent mode of financing higher education, resorted to by two-thirds of students who attend. If upwards of 70 percent of Americans attend college at some point, it thus shackles not an unfortunate few but half the rising population.

Amounts. Indenture was a common practice in seventeenth-century England, but its terms were relatively short, typically a year, and closely regulated by law. The innovation of the Virginia Company, to garner cheap labor in the colonies, extended the practice of indenture to America, but at a much higher obligation of four to seven years, because of the added cost of passage and boarding immigrants, and also the added cost of the brokerage system that arose around it.

Student debt has similarly morphed from relatively small amounts to sizeable ones. The average federal loan debt of a graduating senior in 2008 was $24,000. That was a marked rise from ten years before, but even more tellingly, it was an astronomical rise from twenty-five years ago, when average federal loan debt was less than $2,000. Also consider that many people have significantly more than the average debt—25 percent of federal borrowers had more than $30,000 in student loans, and 14 percent owed more than $40,000 in 2008. Added to federal loans are charge cards, which averaged $4,100 for graduating seniors in 2008, and private loans, which by 2008 were taken by 14 percent of students (up from 1 percent in 1996) and totaled $17.1 billion, a disturbingly large amount in addition to the $68.6 billion for federal loans. Finally, for more than 60 percent of those continuing their education, graduate student debt more than doubled in the past decade, to a 2008 median of about $25,000 for master’s degrees, $52,000 for doctorates, and $80,000 for professional degrees. That is on top of undergraduate debt.

Length of term. Student debt is a long-term commitment— standard Stafford Loans amortize over fifteen years. With consolidation or refinancing, the term frequently extends to thirty years—in other words, for many returning students or graduate students, until retirement age. It is not a brief, transitory bond, say, of a year for those indentured in England, or of 1980s student debtors, who might have owed $2,000.

Transport to work. Student indebtedness is premised on the idea of transport to a job—now the figurative transport over the seas of higher education to attain the shores of credentials deemed necessary for a middle-class job. The cost of transport is borne by the laborer, so, in effect, an individual has to pay for the opportunity to work. If you add the daunting number of hours that students work, one twist of the current system is that servitude begins on ship. Undergraduates at state universities work more than twenty hours a week, according to Marc Bousquet’s work. Tom Mortenson, an education policy analyst, provides a telling comparison of hours a week required at minimum wage to pay tuition, which have grown roughly from twenty hours a week before 1980 to more than fifty hours a week now at public universities and colleges, and from about forty hours to a stunning 130 at private institutions.

Personal contracts. “Indenture” designates a practice of making contracts before signatures were common (they were torn, the tear analogous to the unique shape of a person’s bite, and each party held half, so they could be verified by their match); student debt reinstitutes a system of contracts that bind a rising majority of Americans. Like indenture, the debt is secured not by property, as most loans such as those for cars or houses are, but by the person. Student loan debt “financializes” the person, in the phrase of social critic Randy Martin, who diagnoses this strategy as a central one of contemporary venture capital, displacing risk to individuals rather than employers or society. It was also a strategy of colonial indenture.

Limited recourse. Contracts for federal student loans stipulate severe penalties and are virtually unbreakable, forgiven not in bankruptcy but only in death, and they are enforced by severe measures, such as garnishing wages and other legal sanctions, with little recourse. In England, indenture was regulated by law and servants had recourse in court, but one of the pernicious aspects of colonial indenture was that there was little recourse in the new colonies. Alan Collinge, founder of the grassroots organization Student Loan Justice and author of The Student Loan Scam, has proposed that student debt be forgiven in bankruptcy as any other personal loan would be.

Class. Student debt primarily bears on those with less family wealth, just as indenture drew on the less-privileged classes. That this would be a practice in early modern Britain, before modern democracy, is not entirely surprising; it is more disturbing in the United States, where we eschew the determining force of class. The one-third of students without student debt face much different futures, and are far more likely to pursue graduate and professional degrees (for example, three-quarters of those receiving doctorates in 2004 had no undergraduate debt, and, according to a 2002 Nellie Mae survey, 40 percent of those not pursuing graduate school attributed their choice to debt).

Youth. Student debt applies primarily to younger people, as indenture did. One of the more troubling aspects of student debt is that it is not an isolated hurdle but often the first step down a slope of debt and difficulty, as Tamara Draut, vice president of policy and programs at Demos, shows in Strapped: Why America’s 20- and 30-Somethings Can’t Get Ahead. Added to that burden are shrinking job prospects and historically higher housing payments. The American dream, and specifically the post–World War II dream of equal opportunity opened by higher education, has been curtailed for many of the rising generation.

Brokers. Colonial indenture prompted a system in which merchants or brokers in England’s ports signed prospective workers, then sold the contracts to shippers or colonial landowners, who in turn could resell the contracts. Student debt similarly has fueled an extensive financial services system. The lender pays the fare to the college, and thereafter the contracts are circulated among Sallie Mae, Nellie Mae, and others. Sallie Mae was created as a federal nonprofit corporation, but it became an entirely private (and highly profitable) corporation in 2004.

State policy. The British Crown gave authority to the Virginia Company; the US federal government authorizes current lending enterprises and, even more lucratively for banks, underwrites their risk in guaranteeing the loans (the Virginia Company received no such largesse and went bankrupt). Since the 1990s, federal aid has funneled more to student loans than any other form of aid. Loans might be helpful, but they are a rather ambivalent form of “aid.”

These points show the troubling overlap of indentured servitude and student indebtedness. While indenture was more direct and severe, akin to placing someone in stocks, it was the product of a rigidly classed, semifeudal world that predated modern democracies. Student debt is more flexible, varied in application, and amorphous in effects—a product of the postmodern world—but it revives the spirit of indenture in promulgating class privilege and class subservience. What is most troubling is that it represents a shift in basic political principle. It turns away from the democratic impetus of modern American society, which promoted equality through higher education, especially after World War II. The 1947 Report of the President’s Commission on Education, which ushered in the vast expansion of our colleges and universities, emphasized that “free and universal access to education must be a major goal in American education.” Otherwise, the commission warned, “if the ladder of educational opportunity rises high at the doors of some youth and scarcely rises at the doors of others, while at the same time formal education is made a prerequisite to occupational and social advance, then education may become the means, not of eliminating race and class distinctions, but of deepening them.”

The commission’s goal was not only to promote equality but also to strengthen the United States—and, by all accounts, American society prospered. Current student debt, encumbering so many of the rising generation, has built a roadblock to the American ideal, squanders the resource of those impeded from pursuing degrees who otherwise would make excellent doctors or professors or engineers, and creates a culture of debt and constraint.

The arguments for the rightness of student loan debt are similar to the arguments for the benefits of indenture. One holds that it is a question of supply and demand—many people want higher education, thus driving up the price. This view doesn’t hold water because the demand for higher education in the years following World War II through the 1970s was proportionately the highest of any time, as student enrollments doubled and tripled, but the supply was cheap and largely state funded. Then, higher education was much more substantially funded through public sources, both state and federal; now the expense has been privatized, transferred to students and their families.

University of Chicago economist David Galenson argues in his work on colonial servitude that “long terms did not imply exploitation” because those terms were only fitting for the high cost of transport; because more productive servants, or those placed in undesirable areas, could lessen their terms; and because some servants went on to prosper. He does not mention the high rate of death, the many cases of abuse, the draconian extension of contracts by unethical planters, or simply what term would be an appropriate maximum for any person in a free society to be bound, even if he or she agreed to the contract. Galenson also ignores the underlying political questions: Is it appropriate that people, especially those entering the adult world, might take on such a longterm constraint? Can people make a rational choice for a term they might not realistically imagine? Even if one doesn’t question the principle of indenture, what is an appropriate cap for its amounts and term? One of the more haunting findings of the 2002 Nellie Mae survey was that 54 percent said that they would have borrowed less if they had to do it again, up from 31 percent ten years before, which is still substantial (and, one can extrapolate, increased from 1980). The percentage of borrowers making this informed judgment will surely climb as debt continues to rise.

Some economists justify college student loan debt in terms similar to Galenson’s. One prominent argument holds that because college graduates have averaged roughly $1 million more in salary over the course of their careers than those with less education, it is rational and right that they accumulate substantial debt to start their careers. However, while many graduates make statistically high salaries, the experiences of those who have taken on debt vary a great deal: some accrue debt but don’t graduate; some graduate but, with degrees in the humanities or education, for example, are unlikely to make a high salary; more and more students are having difficulty finding a high-paying job; and the amount that people who have a college degree make over a lifetime has been declining. A degree is no longer the guaranteed ticket to wealth that it once was. An economic balance sheet also ignores the fundamental question of the ethics of requiring debt of those who desire higher education, as well as the fairness of its distribution to those often younger and less privileged.

Over the past few years, there has been more attention to the problem of student loan debt, but most of the solutions, such as Income-Based Repayment, or IBR, are stopgaps that don’t impinge on the basic terms of the system. The system needs wholesale change.

College student loan debt perverts the aims of higher education, whether those aims are to grant freedom of intellectual exploration, to cultivate merit and thereby mitigate the inequitable effects of class, or, in the most utilitarian scheme, to provide students with a head start into the adult work world. In practice, debt shackles students with long-term loan payments, constraining their freedom of choice of jobs and career. It also constrains their everyday lives after graduating, as they bear the weight of the monthly tab that stays with them long after their college days. The AAUP should consider student debt a major threat to academic freedom and make the abolition of student debt one of its major policy platforms.

A Note on Sources

The major source of data on student debt is the Digest of Education Statistics for postsecondary education published by the National Center for Education Statistics of the US Department of Education. The center conducts the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study every four years; the most recent data are from 2007–08. The Project on Student Debt publishes useful reports digesting and processing information related to key aspects of student debt. The loan industry also collects a good deal of information—for example, Sallie Mae’s How Undergraduates Use Credit Cards (2009)—about the contiguous issue of charge-card debt.

Jeffrey J. Williams writes on contemporary fiction, modern criticism and theory, and the university. He is a coeditor of the Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism and was editor of the minnesota review from 1992 to 2010. He is professor of English and of literary and cultural studies at Carnegie Mellon University. His e-mail address is jwill@andrew.cmu.edu.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)